Vesicoureteric Reflux

The urinary system consists of the kidneys, the bladder and ureters. The kidneys filter the blood to remove waste products and form urine. The urine flows from the kidneys down through the ureters to the bladder in a one way direction.

The ureters tunnel through the wall of the bladder at an angle to form a flap that acts as a valve. The valves between the ureters and bladder prevent urine flowing backwards into the ureters, so that all the urine in the bladder is passed in one go, as the urine cannot travel anywhere else. As the urine leaves the bladder at a high pressure, the valves stop this high pressure being passed on to the kidneys.

What is vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR)?

Vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR) occurs when the valve between the ureters and the bladder is not working properly, allowing urine to flow backwards into the ureters. Depending on the severity of the VUR, sometimes the urine can flow backwards as far as the kidneys. If infected urine flows into the kidneys, this can damage them.

What are the symptoms of VUR?

Sometimes VUR can be diagnosed before birth when an ultrasound scan shows that one or both of a baby’s kidneys look swollen and larger than usual (hydronephrosis). VUR is one of the conditions that cause hydronephrosis.

When VUR is diagnosed after birth, it is usually suspected if a child has repeated urine infections. Symptoms of a urine infection can include: burning sensation during urination, urinating more often than usual, abdominal pain, a high temperature, vomiting, reduced appetite or foul smelling urine. Some children also present with recurrent diarrohea or with poor weight gain. If a child has VUR, urine infections can damage the kidneys, as the urine flowing backwards towards them contains bacteria. Kidney damage can cause high blood pressure in later life or if untreated, may lead to kidney failure.

How is VUR diagnosed?

VUR is diagnosed and monitored using two particular scans:

- Ultrasound scans are used to diagnose hydronephrosis before birth and to check the structure of the bladder, ureters and kidneys after birth.

- The other test is called a micturating / voiding cysto-urethrogram (MCUG / VCUG). This uses a liquid that shows up on x-rays, which is put inside the bladder through a catheter (thin, plastic tube) inserted into the urethra. Once the bladder is full of this liquid, the child urinates while being scanned. This shows whether all the liquid is being passed through the urethra, or whether any of it is flowing backwards through the ureters towards the kidneys.

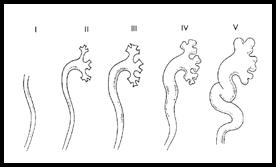

The MCUG / VCUG test is also used to ‘grade’ the degree of reflux, according to its severity; grade 1 is the least severe form of VUR, where urine is flowing back up the ureters but is not reaching the kidneys and grade 5 is the most severe, where a great deal of urine is reaching the kidneys, making the ureter and kidney swollen. VUR is also described as ‘unilateral’ or ‘bilateral’ depending on whether one kidney (unilateral) is affected or both (bilateral).

Grades of Vesicoureteric Reflux

Bilateral Vesico ureteric reflux seen on MCU

What causes VUR?

In many children, the tunnel through the bladder wall is not long enough, so the valve does not work properly, but this can improve as the child grows. In some children, the ureters enter the bladder in a higher position than normal, which also means that the valve does not work properly; this is less likely to improve as the child grows. Other children, particularly boys, may have a blockage in the urethra (posterior urethral valves) causing VUR.

How common is VUR?

VUR occurs in about one in every 100 children. If one child in a family has VUR, there is a chance that the other children could have VUR too, so monitoring might be suggested for brothers and sisters. VUR is usually diagnosed in under fives; it is much less common in older children, who may have outgrown the problem.

How can VUR be treated?

We treat VUR using medicines at first. Usually, a low dose of antibiotics is given on a long-term basis. This prevents urinary tract infections, which in turn, prevents any damage to the kidney caused by infected urine flowing backwards into them. Treatment with antibiotics gives many children the opportunity to outgrow VUR.

Children with VUR who are taking antibiotics will need to give regular urine samples, to be checked for any urine infections, particularly at an early stage. Ultrasound scans are often used to check that the kidneys are growing properly. Nuclear scans also are done to see how much damage is caused to the kidneys by the reflux.

Children who continue to have urinary tract infections despite the antibiotics, or still have severe reflux after the age of five years old might need an operation to correct the problem causing VUR. In this operation, called ureteric reimplantation, the ureters are disconnected from the bladder and re-attached at an angle to create a valve. Now a day, this surgery can also be done endoscopically.

Consequences of VUR?

Untreated VUR may lead to problems like poor weight gain, poor appetite, urinary tract infections and late onset hypertension or end stage renal failure.